http://www.southasiaanalysis.org/papers43/paper4246.html

http://www.southasiaanalysis.org/papers43/paper4246.html

[ In sum, TAPI is the finished product of the US invasion of Afghanistan... It consolidates NATO's political and military presence in the strategic high plateau that overlooks Russia, Iran, India, Pakistan and China. TAPI provides a perfect setting for the alliance's future projection of military power for "crisis management" in Central Asia.....]

What the summit meeting of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) at Lisbon last month brought to mind almost instinctively was that the persistent rumors about the alliance's death were indeed greatly exaggerated. The striking thing was the degree of internal unity and outward determination among the alliance's 28 members.

In recent years, derisive dismissals have featured galore in international discourse about the "dysfunctional irrelevance" of NATO and an alliance characterized as a "Cold War relic". In South Asia - Indian, in particular - this almost resulted in an intellectual ellipsis while dwelling on the overall United States regional strategies in the overlapping Afghanistan-Pakistan conflicts. In fact, NATO hardly figured in the Indian discourses on Afghanistan as an issue of consequence.

Facile impressions gathered in the South Asian strategic community that the US was desperately seeking an "exit strategy" in Afghanistan and was about to "cut and run" from the Hindu Kush.

The NATO summit in Lisbon at the end of November, therefore, came as an eye-opener for South Asians. Voices in the transatlantic space that questioned the continued the raison d'etre of the alliance have fallen completely silent.

Equally, alliance members of both Old and New Europe seem to have recognized that NATO has successfully maneuvered though a transitional phase and completed a process of adjustment in the post-Cold War era. Fundamental divergences in matters of alliance policy are no more.

Unscathed psyche

Quite obviously, the alliance is well on the way to transforming into a global political-military role, and it is forward-looking. There are skeptical voices still that in an era of European austerity, a question mark ought to be put on the alliance's ambitions. European cutbacks in military deployment and rigorous savings programs in defense budgets should not be overplayed, either. NATO is by far today the most powerful military and political alliance in the world.

The US has always been the main provider of the alliance's budget - almost 75% currently - as well as its "hard power". The perceived widening of the US-Europe "divide", however, presents a complex scenario as regards the alliance's evolution as a security organization in the 21st century.

As NATO secretary-general Anders Fogh Rasmussen underlined at the Lisbon summit, "The United States would look elsewhere for its security partner." A kind of "division of labor" in international interventions becomes necessary for the US. The Iraq war showed that it is already happening.

The various partnership programs of NATO in Central Asia and the Gulf Cooperation Council and the Mediterranean regions can be viewed as part of the overall approach to take recourse to other states or groups of states to promote the Euro-Atlantic interests globally.

In a manner of speaking, the "concepts" of power are expanding and NATO is seeking ways and means to eliminate unwanted duplications so as to coordinate more efficiently. At any rate, the handwringing over NATO's impending retreat from the world arena as a military alliance pretty much ended in Lisbon.

On the other hand, it has been replaced by an unequivocal acceptance of the continued raison d'etre of the trans-Atlantic alliance - and the US's leadership role in it - as well as the need of a robust search for partnerships in other regions. Clearly, the US will continue to give primacy to its transatlantic security partnership and intends to use NATO as a key instrument for exerting influence globally as well as for preventing the emergence of any independent power center that challenges its preeminence.

US President Barrack Obama's tour of the Asian region in November (just before NATO gathered in Lisbon), which included stops in India, Indonesia and South Korea, and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton's extensive tours of the members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and the Asia-Pacific region in recent months underscore that the US is bolstering defense ties in the region and scouting for underpinnings for the future expansion of NATO's partnerships in the region.

The thrust of the US strategy is quite clear. To quote former US secretary of state Madeline Albright, who headed NATO's Task Force to develop its new Strategic Concept adopted at the Lisbon summit, "[The] alliance is a solid house that would benefit from new locks and alarm system."

Rasmussen corroborated that the Lisbon summit's objective was to "ensure that NATO is more effective and more efficient" than ever before. He added: "More effective, because NATO will invest in key capabilities like missile defense, cyber-defense and long-range transport. More engaged, because NATO will reach out to connect with our partners around the globe, countries and other organizations. And more efficient, because we are cutting fat, even as we invest in muscle."

These objectives constituted the foundation of the New Strategic Concept for the coming decade adopted in Lisbon. As the objectives were fleshed out, three tasks got highlighted: collective defense, comprehensive crisis management and cooperative security. The Strategic Concept states, "We are firmly committed to preserve its [NATO's] effectiveness as the globe's most successful political-military alliance."

The core task will be to defend Europe and ensure the collective security of its 28 members, while the Strategic Concept envisages NATO's prerogative to mount expeditionary operations globally.

The document explicitly says, "Where conflict prevention proves unsuccessful, NATO will be prepared and capable to manage ongoing hostilities. NATO has unique conflict-management capacities, including the unparalleled capability to deploy and sustain robust military forces in the field."

The alliance pledged to strengthen and modernize its conventional forces and to develop the full range of military capabilities. It will remain a nuclear alliance while developing a missile defense capability. The Strategic Concept reaffirmed that NATO will forge partnerships globally and reconfirmed the commitment to expand its membership to democratic states that meet the alliance's criteria.

To be sure, the Western alliance's habitation in the South Asian region will be shaping the geopolitics of the region in the coming period, and vice versa.

The discourses in the region blithely assumed until recently that NATO would have no appetite for far-flung operations and was desperately looking for an exit strategy in Afghanistan. On the contrary, what stood out from the Lisbon summit is that the NATO psyche comes out of the bloody war unscathed and, conceivably, the US may succeed in attaining a politically acceptable outcome for NATO's continued engagement in Afghanistan (and Pakistan).

'Robust, enduring partnership' with Kabul

Several questions arise as NATO transforms as a global security organization and establishes its long-term presence in the South Asian region. Will NATO be prepared to subject itself to the collective will of the international community as represented in the UN Charter, or will Article 5 of its charter (an armed attack against one or more [NATO members] in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all ....) continue to be the overriding principle?

There are huge uncertainties regarding regional security in South Asia. Border issues and beliefs and resentments expressed in Manichean categories, etc, are ransacking the security environment in the region.

The Western alliance has great experience in offering reassuring collective security and promoting reconciliation between the former Allied and Axis powers, as the difficult termination of Franco-German hostility shows. Will NATO aspire to be a framework for stabilizing the highly volatile and dangerous geopolitical situation in the South Asian region?

NATO is assertively proclaiming its preeminence as a security organization on the global plane and is yet sticking to its trans-Atlantic moorings against a backdrop where Europe's (the Western world's) dominance in international politics is on the wane and there is a shift in the locus of political and economic activity shifting away from the North Atlantic toward Asia.

To quote Zbigniew Brzezinski, "Whether they are "rising peacefully" (a self-confident China), truculently (an imperially nostalgic Russia) or boastfully (an assertive India, despite its internal multiethnic and religious vulnerabilities), they all desire a change in the global pecking order. The future conduct of an relationship among these three still relatively cautious revisionist powers will further intensify the strategic uncertainty."

From a seemingly reluctant arrival in Afghanistan seven years ago in an "out-of-area" operation as part of the UN-mandated ISAF [International Security Assistance Force], with a limited mandate, NATO is suo moto stepping out of the ISAF, deepening its presence and recasting its role and activities on a long-term basis. South Asian security will never be the same again.

At the Lisbon summit, NATO and Afghanistan signed a declaration as partners. The UN didn't figure in this, and it is purely bilateral in content. The main thrust of the declaration is to affirm their "long-term partnership" and to build "a robust, enduring partnership which complements the ISAF security mission and continues beyond it."

It recognizes Afghanistan as an "important NATO partner… contributing to regional security". In short, NATO and Afghanistan will "strengthen their consultation on issues of strategic concern" and to this end develop "effective measures of cooperation" which would include "mechanisms for political and military dialogue… a continuing NATO liaison in Afghanistan… with a common understanding that NATO has no ambition to establish a permanent military presence in Afghanistan or use its presence in Afghanistan against other nations."

NATO and Afghanistan will initiate discussion on a Status of Forces Agreement within the next three years. The Declaration also provides for the inclusion of "non-NATO nations" in the cooperation framework.

The Lisbon summit, in essence, confirmed that the NATO military presence in Afghanistan will continue even beyond 2014, which has been the timeline suggested by Afghan President Hamid Karzai for Kabul to be completely in charge of the security of the country.

President Obama summed up: "Our goal is that the Afghans have taken the lead in 2014 and in the same way that we have transitioned in Iraq, we will have successfully transitioned so that we are still providing a training and support function."

NATO may undertake combat operations beyond 2014 if and when a need arises. As Obama put it, all that is happening by 2014 is that the "NATO footprint in Afghanistan will have been significantly reduced. But beyond that, it's hard to anticipate exactly what is going to be necessary… I'll make that determination when I get there."

Clearly, the billions of dollars that have been pumped into the upgrading of Soviet-era military bases in Afghanistan in the recent period and the construction of new military bases, especially in Mazar-i-Sharif and Herat regions bordering Central Asia and Iran, fall into perspective.

Reaching out to India

As the biggest South Asian power, India seems to have been quietly preparing for this moment, backtracking gradually from its traditional stance of seeking a "neutral" Afghanistan free of foreign military presence. Of course, the bottom line for the Indian government is that the foreign policy should be optimally harmonized with US regional strategies. Therefore, all signs are that India as a "responsible regional power" will not fundamentally regard the NATO military presence in zero-sum terms.

Several considerations will influence the Indian approach in the coming period. One, India is an direct beneficiary of the US's "Greater Central Asia" strategy, which aims at drawing that region closer to South Asia by creating new linkages, especially economic.

Second, India has no strong views regarding NATO's partnership programs in Central Asia - unlike Russia or China, which harbor disquiet over it. At a minimum, there is no conflict of interest between India and NATO on this score. On the outer side, India would see advantages if NATO indeed works on a strategy to "encircle" China in Central Asia. The US military base in Manas, Kyrgyzstan, the induction of a fleet of AWACS (airborne warning and control system) aircraft into Afghanistan, and so forth give the alliance certain capability already to monitor the Xinjiang and Tibet regions where China has located its missiles targeted at India.

It is within the realms of possibility that NATO would at a future date deploy components of the US missile defense system in Afghanistan. Ostensibly directed against the nearby "rogue states", the missile defense system will challenge the Chinese strategic capability. Meanwhile, India is also developing its missile defense capabilities and future cooperation with the US in the sphere is on the cards.

The stated Indian position so far has been that it will not identify with any military alliance or bloc. Having said that, it is also important to note that India enjoys observer status in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization [SCO] and is seeking full membership in it. There has been a dichotomy insofar as incrementally, India's contacts with NATO have been gathering steam.

Contacts with NATO at the level of the Indian military establishment have been unobtrusive but have also become a regular affair. NATO delegations have been regularly interacting with Indian think tanks and the defense and foreign policy establishment in Delhi. Unsurprisingly, much of this interaction remains sequestered from public view even as the Indian establishment continues to mouth for public consumption its traditional aversion toward military alliances and blocs.

Top Indian officials have crafted a new idiom calling for an "inclusive" security architecture for South Asia, a firm wedge leaving the door open for the inclusion of the extra-regional entities such as the US and/or NATO at some point. India probably perceives such "inclusiveness" as useful and necessary to balance China's rapidly growing profile in the South Asian region.

Most certainly, India harbors the hope that a NATO presence in Afghanistan for the foreseeable future may not be a bad thing to happen, after all. Delhi regards NATO's continued participation in the Afghanistan-Pakistan conflicts to be a bulwark against the possibility of a Taliban takeover in Afghanistan.

Also, it is useful for India that the Western alliance continues to be seized of the paradigm (from the Indian perspective) that the core issue of regional security in South Asia is the Pakistani military's policy of using the Taliban militants to gain "strategic depth" and of conceiving terrorism as an instrument of state policy.

India is acutely conscious that the US sensitivities regarding its interests are at odds with NATO forces' pressing need to elicit a full and genuine political and military support from Pakistan to work out an Afghan settlement that can withstand the threat of a Taliban takeover in Kabul.

Again, given India's rivalry with China, Delhi watches with unease the US efforts to engage China in a geopolitical dialogue over Pakistan's long-term security, although logically, it ought to feel a stake in avoiding a regional upheaval in Pakistan and ought to welcome a constructive role by China in helping to stabilize the situation in Pakistan.

In the year ahead, the thing to watch will be any paradigm shift in the direction of a cooperative NATO outreach toward the Moscow-led Collective Security Treaty Organization [CSTO]. Russia has been assiduously cultivating a strand of thinking within the alliance that joint security undertakings with CSTO could foster and even render optimal NATO's effectiveness on a trans-regional basis.

So far, the US has remained adamant about not conceding Russia's implicit claim of a sphere of influence in the post-Soviet space. The CSTO summit meeting on December 10 points toward Moscow going ahead with the build up of its alliance also as a global security organization. Moscow seems to have concluded that any NATO enlistment of CSTO cooperation in the explosive area of the Afghan problem will be a protracted process, if at all - leave alone formal, direct links.

With India, on the other hand, the US has been promoting interoperability, discussing the potentials of cooperation in meeting mutually threatening contingencies and developing genuine strategic cooperation. The massive induction of US-made weapons systems into the Indian armed forces that can be expected in the coming period will accelerate these processes, and it is entirely conceivable that at some point India may overcome its lingering suspicions regarding Western domination and establish formal links with NATO with a modest first step of forming a joint council.

This train of thinking in Delhi will be significantly influenced by any pronounced eastward shift in NATO's center of gravity toward the Asia-Pacific region involving the East Asian powers, especially China.

Reassuring Pakistan

The conviction in New Delhi is that NATO interests in Afghanistan and Pakistani (military) objectives are ultimately irreconcilable and sooner rather than later the US will have to address the contradiction. India could be underestimating the criticality of Pakistan's role in the US regional strategy.

The fact remains that geography dictates that Pakistan will always play a major role in ensuring the stability of Afghanistan. Arguably, India can be kept out of conflict resolution in Afghanistan, but Pakistan cannot be. Even countries that are friendly toward India - Russia, Turkey, Iran, Tajikistan - find it expedient to work with Pakistan. And towards that end, they are willing to acquiesce with Islamabad's "precondition" of keeping India at arm's length.

In fact, India doesn't figure in a single regional format involved in the search for a political settlement in Afghanistan. Its involvement almost entirely devolves upon its cogitations with the US.

There are any number of reasons why Pakistan's centrality in any search for conflict resolution in Afghanistan needs to be acknowledged. Afghanistan's subsistence economy cannot even survive today without trade and transit provided by Pakistan.

The Afghan political elites, especially the Pashtun elites, view Pakistan as their single most important interlocutor. They may seek out India as a "balancer" when the Pakistani intrusiveness or belligerence becomes too much for them, but ultimately, they have to have dealings with Pakistan.

Again, the Afghan insurgency is Pashtun-driven and the tribal kinships across the Pakistan-Afghanistan border are historical. Close to three million Afghan (Pashtun) refugees live in Pakistan. Pakistan wields decisive influence over a range of Afghan insurgent groups - Quetta Shura, Haqqani network, Hezb-i-Islami - and maintain extensive contacts with even groups that previously belonged to the Northern Alliance and spearheaded the anti-Taliban resistance, in particular, the "Mujahideen" leaders who fought the Soviet occupation such as Sibghatullah Mojaddidi, Burhanuddin Rabbani, Rasul Sayyaf, and others.

Needless to say, the terrorist nexus operating in the region includes Pakistani groups, and the Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence continues to patronize some of them - and increasingly Pakistan is prepared to admit openly that they are its "strategic assets" inside Afghanistan to safeguard its long-term interests. Pakistan has invested heavily in men and material during the past two decades to gain "strategic depth" in Afghanistan and appears today to be every bit determined to influence any Afghan settlement.

Over and above, NATO and the US heavily depends on the two routes through Pakistan - via North-West Frontier province and Baluchistan - to supply the troops in Afghanistan.

The WikiLeaks disclosures have shown that the relationship between Pakistan and the US has been extremely complex. On the one hand, the US wields enormous influence on the Pakistani elites and the US diplomats blatantly interfere in Pakistan's domestic affairs - and the Pakistani politicians unabashedly seek American support for their shenanigans. But on the other hand, everything points to the limit of American power in Islamabad.

Pakistan surely has an uncanny knack to hunker down and even defy the US when it comes to safeguarding its core concerns and vital interests. Having said that, while Pakistan may behave in a exasperating way - full of doublespeak and double dealings - and at times shows signs of "strategic defiance", Pakistan also is extremely pragmatic and is finely tuned into the US's critical needs at the operational level, as the policy on the US drone attacks in the tribal areas testify.

WikiLeaks singles out two instances at least during the past year when the Pakistani military actually allowed the US forces to conduct operations inside Pakistan, completely disregarding the vehement "anti-Americanism" sweeping the country and quite contrary to its vehement public stance against any such erosion of Pakistani sovereignty and territorial integrity.

The heart of the matter is that both Pakistan and the US are under strong compulsion to reconcile their divergent approaches and work toward an Afghan settlement. The main sticking point at the moment devolves upon the strategy currently pursued by US commander David Petraeus who hopes to degrade the insurgents so that the Americans can eventually talk with the Taliban leadership from a position of strength.

Pakistan has the upper hand here since time is in its favor. Therefore, the likelihood of the US-Pakistani discords reaching a flashpoint in any given situation simply doesn't arise.

A finished product of Afghan war

This geopolitical reality is very much linked to NATO's future role in Afghanistan. US strategy toward an Afghan settlement visualizes the future role for NATO as the provider of security to the Silk Road that transports the multi-trillion dollar mineral wealth in Central Asia to the world market via the Pakistani port of Gwadar. In short, Pakistan is a key partner for NATO in this Silk Road project.

The Afghan-Pakistan trade and transit agreement concluded in October was a historic milestone and was possible only because of Washington's sense of urgency. It stands out as the late Richard Holbrooke's fine legacy. Actually, Holbrooke, the US diplomacy point man in the region, sought and obtained India's tacit cooperation in these negotiations leading to the Afghan-Pakistan agreement, which shows the extent to which Delhi is also counting on Washington to smoothen the edges of the Afghan-Pakistan-India triangular equations regarding trade and transit issues.

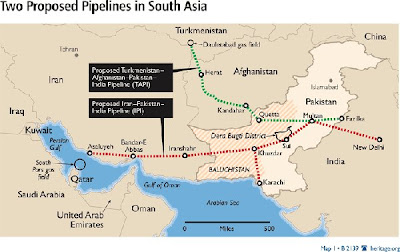

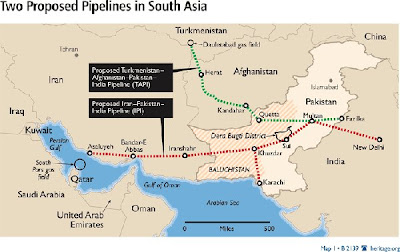

Without doubt, Pakistan is assured of a key role in the US regional strategy, which will keep foreign money flowing into Pakistan's economy. The Pakistani military will willingly accelerate the existing partnership programs with NATO and even upgrade them. The resuscitation of the Silk Road project to construct an oil and gas pipeline connecting Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India (the TAPI pipeline) will need to be seen as much more than a template of regional cooperation.

The pipeline signifies a breakthrough in the longstanding Western efforts to access the fabulous mineral wealth of the Caspian and Central Asian region. Washington has been the patron saint of the TAPI concept since the early-1990s when the Taliban was conceived as its Afghan charioteer. The concept became moribund when the Taliban regime was driven out of power from Kabul.

Now the wheel has come full circle with the project's incremental resuscitation since 2005, running parallel with the Taliban's fantastic return to the Afghan chessboard. TAPI's proposed commissioning coincides with the 2014 timeline for ending the NATO "combat mission" in Afghanistan. The US "surge" is concentrating on Helmand and Kandahar provinces through which the TAPI pipeline will eventually run. What an amazing string of coincidences!

The NATO Strategic Concept adopted in the Washington summit in April 1999 has outlined that disruption of vital resources could impact on the alliance's security interests. Since then, NATO has been deliberating on its role in energy security, clarifying its role in the light of shifting global political and strategic realities.

The Bucharest summit of the alliance in April 2008 deliberated on a report titled "NATO's Role in Energy Security", which identified the guiding principles as well as options and recommendations for further activities. The report specifically identified five areas where NATO can play a role. These included: information and intelligence fusion and sharing; projecting stability; advancing international and regional cooperation; supporting consequence management; and supporting the protection of critical infrastructure.

The alliance already conducts projects focusing on the Southern Caucasus and Turkey - the Baku-Ceyhan crude oil pipeline and the Baku-Erzurum natural gas pipeline. In August this year, a new division was created within NATO's International Staff to exclusively handle "non-traditional risks and challenges", including energy security, terrorism, and such.

On the map, the TAPI pipeline deceptively shows India as its final destination. What is overlooked, however, is that the route can be easily extended to the Pakistani port of Gwadar and connected with European markets, which is the ultimate objective.

The onus is on each of the transit countries to secure the pipeline. Part of the Afghan stretch will be buried underground as a safeguard against attacks and local communities will be paid to guard it. But then, it goes without saying that Kabul will expect NATO to provide security cover, which, in turn, necessitates long-term Western military presence in Afghanistan.

In sum, TAPI is the finished product of the US invasion of Afghanistan. It consolidates NATO's political and military presence in the strategic high plateau that overlooks Russia, Iran, India, Pakistan and China. TAPI provides a perfect setting for the alliance's future projection of military power for "crisis management" in Central Asia.....

| TAPI is in actuality a Silk Road project connecting Central Asia to the West via Gwadar, which will make Pakistan the U.S.'s gateway to Central Asia. |

The significance of the signing of the intergovernmental agreement on the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India gas pipeline project (TAPI) on December 11 in Ashgabat cannot be overstated. It can only be captured if one says with a touch of swagger that TAPI has been the most significant happening in the geopolitics of the region in almost a decade since America invaded Afghanistan.

The heart of the matter is that TAPI is a Silk Road project, which holds the key to modulating many complicated issues in the region. It signifies a breakthrough in the longstanding U.S. efforts to access the fabulous mineral wealth of the Caspian and the Central Asian region. Afghanistan forms a revolving door for TAPI and its stabilisation becomes the leitmotif of the project. TAPI can meet the energy needs of Pakistan and India. The U.S. says TAPI holds the potential to kindle Pakistan-India amity, which could be a terrific thing to happen. It is a milestone in the U.S.' “Greater Central Asia” strategy, which aims at consolidating American influence in the region.

Washington has been the patron saint of the TAPI concept since the early 1990s when the Taliban was conceived as its Afghan charioteer. The concept became moribund when the Taliban was driven away from Kabul. Now the wheel has come full circle with the incremental resuscitation of the project since 2005 running parallel to the Taliban's fantastic return to the Afghan chessboard. The proposed commissioning of TAPI coincides with the 2014 timeline for ending the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation's “combat mission” in Afghanistan. The U.S. “surge” is concentrating on the Helmand and Kandahar provinces, through which TAPI will eventually run. What stunning coincidences!

In sum, TAPI is the finished product of the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan. Its primary drive is to consolidate the U.S. political, military and economic influence in the strategic high plateau that overlooks Russia, Iran, India, Pakistan and China.

TAPI capitalises on Turkmenistan's pressing need to find new markets for its gas exports. With the global financial downturn and the fall in Europe's demand for gas, prices crashed. Russia cannot afford to pay top dollar for the Turkmen gas, nor does it want the 40 bcm gas it previously contracted to purchase annually. Several large gasfields are coming on line in Russia, which will reduce its need for the Turkmen gas. The Yamal Peninsula deposit alone is estimated to hold roughly 16 trillion cubic metres of gas. But Turkmenistan sits on the world's fourth-largest gas reserves and has its own plans to increase production to 230 bcm annually by 2030. It desperately needs to find markets and build new pipelines.

Thus, Ashgabat is driven by a combination of circumstances to adopt an energy-export diversification policy. In the recent months, the Turkmen leadership evinced interest in trans-Caspian projects but it will remain a problematic idea as long as the status of Caspian Sea remains unsettled. Besides, Turkmenistan has unresolved territorial disputes with Azerbaijan. In November, a second Turkmen-Iranian pipeline went on stream and there is potential to increase exports up to 20 bcm. But then, there are limits to expanding energy exports to Iran or to using Iran as a “regional gas hub” — for the present, at least.

Therefore, Turkmen authorities began robustly pushing for TAPI. The projected 2000-km pipeline at an estimated cost of $7.6 billion will traverse Afghanistan (735 km) and Pakistan (800 km) to reach India. Its initial capacity will be around 30 bcm but that could be increased to meet higher demand. India and Pakistan have shown interest in buying 70 bcm annually. TAPI will be fed by the Doveletabad field, which used to supply Russia.

Ashgabat did smart thinking to accelerate TAPI. The U.S. encouraged Turkmenistan to estimate that this is an enterprise whose time has come. Funding is not a problem. The U.S. has lined up the Asian Development Bank. An international consortium will undertake construction of the pipeline. A curious feature is that the four governments have agreed to “outsource” the execution and management of the project. The Big Oil sees great prospects to participate. The Afghan oilfields can also be fed into TAPI. Kabul awarded its first oil contract in the Amu Darya Basin this week. The gravy train may have begun moving in the Hindu Kush.

On the map, the TAPI pipeline deceptively shows India as its final destination. What is overlooked, however, is that it can easily be extended to the Pakistani port of Gwadar and connected with European markets, which is the core objective. The geopolitics of TAPI is rather obvious. Pipeline security is going to be a major regional concern. The onus is on each of the transit countries. Part of the Afghan stretch will be buried underground as a safeguard against attacks and local communities will be paid to guard it. But then, it goes without saying Kabul will expect the U.S. and NATO to provide security cover, which, in turn, necessitates a long-term western military presence in Afghanistan. Without doubt, the project will lead to a strengthening of the U.S. politico-military influence in South Asia.

The U.S. brought heavy pressure on New Delhi and Islamabad to spurn the Iran-Pakistan-India pipeline project. The Indian leadership buckled under American pressure while dissimulating freedom of choice. Pakistan did show some defiance for a while. Anyhow, the U.S. expects that once Pakistanis and Indians begin to chew the TAPI bone, they will cast the IPI into the dustbin. Pakistan has strong reasons to pitch for TAPI as it can stave off an impending energy crisis. TAPI is in actuality a Silk Road project connecting Central Asia to the West via Gwadar, which will make Pakistan the U.S. gateway to Central Asia. Pakistan rightly estimates that alongside this enhanced status in the U.S. regional strategy comes the American commitment to help its economy develop and buttress its security needs in the long-term.

India's diligence also rests on multiple considerations. Almost all reservations Indian officials expressed from time to time for procrastinating on the IPI's efficacy hold good for TAPI too — security of the pipeline, uncertainties in India-Pakistan relationship, cost of gas, self-sufficiency in India's indigenous production, etc. But the Indian leadership is visibly ecstatic about TAPI. In retrospect, what emerges from the dense high-level political and diplomatic traffic between Delhi and Ashgabat in the recent years is that our government knew much in advance that the U.S. was getting ready to bring TAPI out of the woodwork at some point — depending on the progression of the Afghan war — and that it would expect Delhi to play footsie.

Even Prime Minister Manmohan Singh found time to visit the drab Turkmen capital in a notable departure from his preoccupations with the Euro-Atlantic world. The wilful degradation of India-Iran ties by the present government and Dr. Singh's obstinate refusal to visit Iran also fall into perspective. Plainly put, our leadership decided to mark time and simply wait for TAPI to pop out of Uncle Sam's trouser pocket and in the meantime it parried, dissimulated and outright lied by professing interest in the IPI. The gullible public opinion was being strung along.

To be sure, TAPI is a big-time money-spinner and our government's energy pricing policies are notoriously opaque. Delhi will be negotiating its gas price “separately” with Ashgabat on behalf of the private companies which handle the project. That is certain to be the mother of all energy “negotiations” involving two countries, which figure at the bottom of the world ranking by Transparency International.

Energy security ought to have been worked out at the regional level. There was ample scope for it. The IPI was a genuine regional initiative. TAPI is being touted as a regional project by our government but it is quintessentially a U.S.-led project sheltered under Pax Americana, which provides a political pretext for the open-ended western military presence in the region. As long as foreign military presence continues in India's southwestern region, there will be popular resistance and that will make it a breeding ground for extremist and terrorist groups. India is not only shying away from facing this geopolitical reality but, in its zest to secure “global commons” with the U.S, is needlessly getting drawn into the “new great game.” Unsurprisingly, Delhi no more calls for a neutral Afghanistan. It has lost its voice, its moral fibre, its historical consciousness.

Finally, TAPI is predicated on the U.S. capacity to influence Pakistan. Bluntly speaking, TAPI counts on human frailties — that pork money would mellow regional animosities. But that is a cynical assumption to make about the Pakistani military's integrity.....

The US has now been fighting this war for nine years, and is prepared to continue it for another four; it presently has some 100,000 US soldiers fighting there at an annual cost of some 100 billion dollars. All in order to disrupt, dismantle and defeat al-Qaeda? Al-CIAda? In Afghanistan and Pakistan? The ridiculousness of this proposition compelled Joe Biden a few days later to publicly clarify that he, at least, knows that, whatever the danger from AQ, it doesn’t come from this region.

Whatever the real aim, achieving some kind of military victory in Afghanistan requires, as an essential prerequisite, the suppression of insurgent bases and sanctuaries in Pakistan. This has to be done by Pakistan, since it will not allow the US to do it. The review indicates that the US proposes to continue its past policies to get Pakistan to do this, namely, the carrot of aid and engagement, and the stick of pressure and threats. The administration has obviously not accepted the reality that these will never work, as so clearly enunciated in September 2009 by then US Ambassador in Islamabad, Anne Patterson. The reality is that this Pakistani policy is based on its national security needs, and it will not be bribed or bullied into abandoning it.

The review appears to similarly gloss over the real problem the US faces in Afghanistan, namely, that of governance (or lack thereof). To be able to hand over responsibility for security to Afghans at some stage there has to be a reasonably credible government in place, a government that the bulk of the population accepts. The present government of Hamid Karzai does not meet this test, and there are no grounds for believing that it ever will. The review bypasses this issue by focusing instead on plans for establishing a large Afghan military and police structure. Even if the wishful thinking underlying these expectations were to be largely realised (which is quite doubtful), such a security establishment cannot make up for the lack of effective governance.

The review speaks of “progress” and “notable operational gains” in the war. These obviously refer to the operations being conducted in the south of the country by the additional troops that Obama sent in. Not surprising: if you flood an area with heavily armed, well-supported troops, the insurgents will melt away. The problem is that to hold on to these gains these troop levels have to be maintained, but the American soldiers can’t stay forever, and there is no evidence that Afghan security forces will be able to effectively replace them. Meanwhile, a serious problem is being created by the destructive manner in which US forces have conducted their takeover (mainly in order to minimize their own casualties); this has caused widespread anger among the local population against both the foreign troops and their Afghan sponsors. Securing ground temporarily but losing hearts and minds is not “progress” against an insurgency.

The gap between the Obama administration’s review of the war and the reality on the ground does not matter all that much because the fictions it contains are no bigger than the fiction that the administration controls the war. It provides the resources for it, it enables the war, but it does not control it. That control is in the hands of those powerful groups whose personal and policy interests are served by keeping the United States in a permanent state of war (hot or cold). It is these Perpetual Warriors who will decide when and how to end it. Even the actual conduct of the war is not determined by the administration; the Pentagon and the generals decide that.

So, the Afghan war will go on pretty much as it has so far. With his additional troops Gen Petraeus will secure some parts of the south, but the insurgents will shift to other areas. Pakistan will continue to prevaricate about the sanctuaries (the fact is, even if they wished to root them out, they couldn’t do it, given the practical limitations imposed by their situation). The Afghan army will become bigger; some of its units will become quite good; but it will have no real allegiance to a feckless, corrupt government, which is unlikely to change its ways. Afghans ‒ insurgents, collaborators, and the unfortunates caught in-between ‒ will wait for this empire, too, to weary of this fruitless enterprise, and depart.

One day the Perpetual Warriors will decide that this war no longer pays dividends (perhaps another war offers better returns, or the economy can’t support it any longer), and they will pull the plug on it.

Welcome to the real world.....

http://www.southasiaanalysis.org/papers43/paper4246.html

http://www.southasiaanalysis.org/papers43/paper4246.html

(e)SP_A0012_edited.jpg)